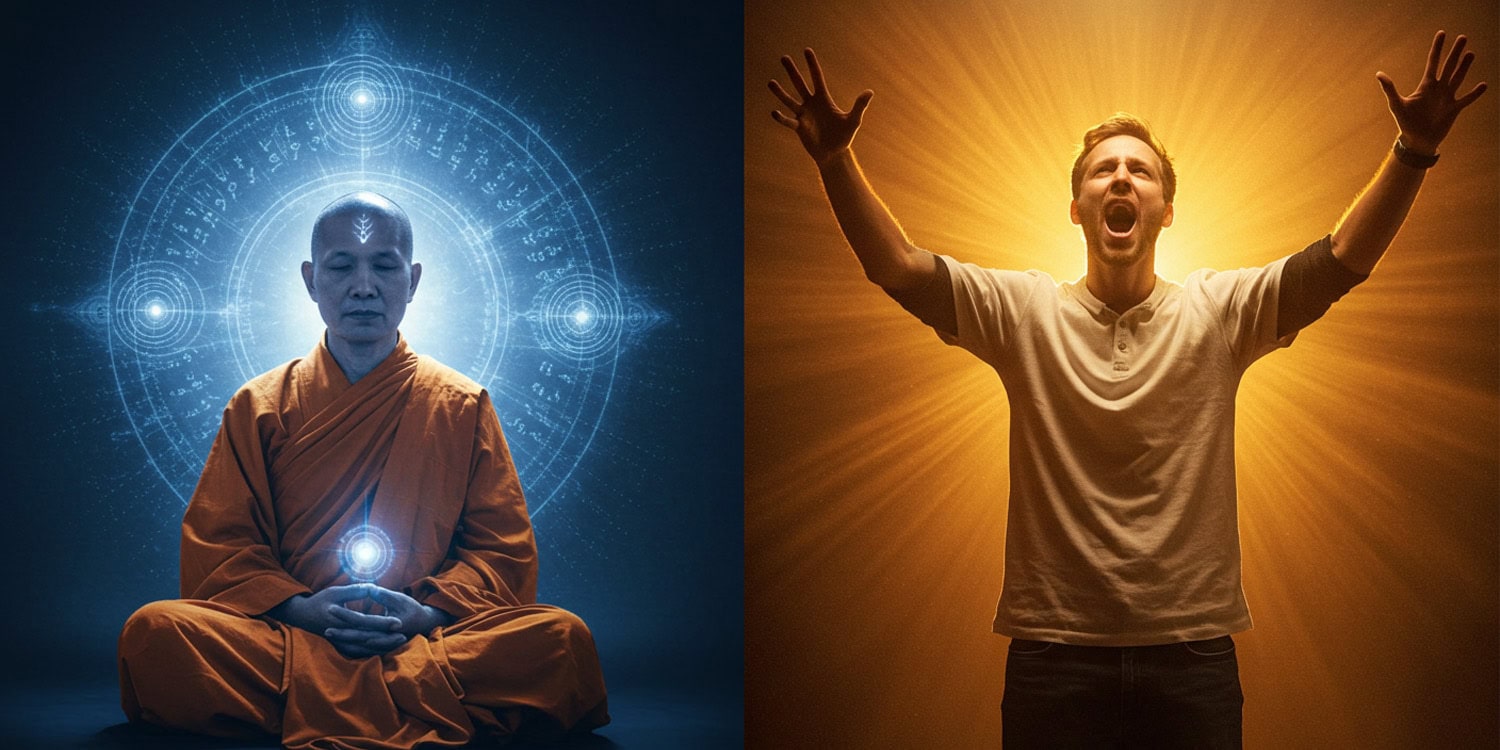

Two spiritual practices that appear vastly different on the surface – the quiet focus of Buddhist jhāna meditation and the emotionally expressive Christian practice of speaking in tongues – may share a common underlying mechanism for achieving deep states of joy and surrender, according to a new study published in American Journal of Human Biology. Researchers discovered that both practices seem to utilize the same mental feedback loop, which they term the “Attention, Arousal and Release Spiral,” to create profound experiences. This finding suggests a surprising commonality between seemingly disparate spiritual traditions in how humans can cultivate intense focus and emotional release.

Buddhist jhāna meditation and the Christian practice of speaking in tongues are, at first glance, strikingly dissimilar. Jhāna meditation, rooted in Buddhist tradition, is characterized by seated stillness, quiet focus, and an outward appearance of profound calm. Practitioners meticulously train their attention, often focusing on the breath, to achieve deep states of absorption marked by stability, peacefulness, and even bliss. Detailed instructions within Buddhist texts guide this practice.

In contrast, speaking in tongues, a practice found in charismatic evangelical Christianity, involves uttering sounds that often seem nonsensical, accompanied by expressive behaviors like cries, laughter, and even dancing. This practice is understood by participants as releasing control of their voice to allow the Holy Spirit to guide their prayer. While inspired by brief mentions in the New Testament and largely passed down orally, particularly within the Black Church, speaking in tongues lacks formal written guidelines and is often described as a spontaneous experience.

The research team, led by Michael Lifshitz at McGill University, along with colleagues from other institutions, wanted to explore the hidden similarities between these practices. They were curious about the inner workings of the mind that help people feel such intense joy and a deep sense of release, despite the outward differences in behavior. The researchers believed that both practices might tap into a common mental cycle that brings about states of deep focus and positive emotion.

To examine this idea, the researchers conducted a study involving detailed interviews with both jhāna meditation practitioners and individuals who practice speaking in tongues. For the jhāna meditation group, researchers interviewed ten individuals who had recently completed a ten-day meditation retreat in Georgia, USA. These participants were trained in jhāna meditation by an experienced American Buddhist teacher. The interviews took place in the weeks following the retreat and focused on their experiences during the practice. For the speaking in tongues group, the researchers drew upon data from existing projects. They utilized interviews with 40 charismatic evangelical Christians in the United States from the Mind and Spirit Project, and interviews with 66 individuals from a neurophenomenological study on prayer. These larger projects provided a rich source of first-person accounts of the speaking in tongues experience.

The researchers employed a method called neurophenomenology, which emphasizes the importance of first-person accounts in understanding inner experiences. This approach recognizes that personal descriptions are not just reflections of inner states but also actively shape those experiences. By gathering detailed descriptions of what practitioners experienced during jhāna meditation and speaking in tongues, the researchers aimed to identify common patterns and underlying mechanisms.

The interviews encouraged participants to describe their experiences in detail, focusing on subtle shifts in their attention, emotions, and sense of control during their respective practices. This focus on the lived experience allowed the researchers to move beyond the surface differences of the two practices and explore potential shared elements at a deeper, experiential level.

The analysis of these interviews revealed a recurring pattern in both jhāna meditation and speaking in tongues, which the researchers termed the Attention, Arousal, and Release Spiral. In jhāna meditation, practitioners focus their attention on a chosen object, such as the breath or a mental image called a nimitta. As concentration deepens, they described how this focused attention leads to feelings of joy and energy. This joy, in turn, seems to reinforce their ability to focus, creating a positive feedback loop. Participants explained that as their attention became more stable on the breath or nimitta, they experienced a diminishing awareness of everyday sensory experiences and thoughts, leading to a profound sense of stillness and steadiness. One participant described this stillness as the disappearance of subtle mental movements, replaced by a deep inner calm.

Crucially, practitioners of jhāna meditation also described a process of “release” that was integral to deepening their meditative state. This release involved multiple aspects, including letting go of distracting thoughts, habitual patterns, and the sense of being in control. They emphasized that intentionally surrendering control of their mental and bodily processes seemed to facilitate relaxation and trust, allowing them to move deeper into the meditative experience. This act of release was not seen as passive but rather as an active yielding, demonstrating faith in the practice and leading to a sense of spacious clarity. Metaphors of “slipping upward” or “sliding into a jacuzzi” were used to describe the experience of entering jhāna, highlighting the effortless and yielding nature of this transition after initial focused effort.

Similarly, in speaking in tongues, practitioners described a process that also involved attention, arousal, and release. They described focusing their attention intensely on God, often accompanied by a sense of passionate devotion and urgency. This focused attention, they reported, often led to heightened emotional and physical arousal, sometimes described as feeling “fire” or “electricity” in their bodies. This arousal was not seen as chaotic but as a manifestation of the Holy Spirit’s presence.

Release was also a key component of speaking in tongues. Practitioners described actively surrendering control, particularly of their speech, as they allowed the Holy Spirit to guide their vocalizations. This release of vocal control often extended to emotional and cognitive release as well, with participants describing intense emotional experiences like crying or shaking. This act of surrender was seen as central to the practice, enabling a deeper connection with God and a sense of profound peace amidst the emotional intensity. Interestingly, even within the high arousal of speaking in tongues, practitioners described moments of “utter calm” and stillness, suggesting that the practice could encompass both energized expression and quiet contemplation.

The researchers propose that this shared Attention, Arousal, and Release Spiral operates through a series of interconnected steps. First, focused attention, whether on the breath in meditation or on God in prayer, increases the clarity and vividness of the object of attention. This heightened clarity, in turn, boosts the brain’s confidence in its perception, leading to positive feelings of joy and pleasure associated with the object of focus. Second, these positive feelings then make attention feel more effortless, creating a feedback loop where joy reinforces attention, and attention intensifies joy. Finally, the intention and act of release, of letting go of control, further deepens this cycle. This release, facilitated by the growing ease and joy, allows for even deeper states of absorption in both practices.

While these findings open up a new way of understanding spiritual practice, the researchers are careful to note some limitations of their study. One limitation is that the study relied heavily on personal reports and interviews. Although these accounts provide rich detail about inner experiences, they can be subjective and influenced by cultural expectations. The study also involved a relatively small group of meditators compared to the much larger community of Christians who speak in tongues. This means that more research is needed to see if the findings hold true in other groups or in more diverse settings. Additionally, the brain scanning methods used in this study provide only a snapshot of the brain’s activity, and further studies are needed to understand how these processes develop over time.

Future research will likely focus on using more detailed brain imaging techniques to capture the dynamic changes in brain activity as the cycle of attention, joy, and release unfolds. The researchers are also interested in exploring how these processes might be used to help people cultivate inner peace and well-being in everyday life.

“If we can understand this process better, we may be able to help more people access deep states of tranquility and bliss for themselves,” said Lifshitz. “In another sense, our findings may help to promote a sense of commonality and mutual respect between spiritual traditions. Despite differences in beliefs, we are all sharing a human experience.”

The study, “The Spiral of Attention, Arousal, and Release: A Comparative Phenomenology of Jhāna Meditation and Speaking in Tongues,” was authored by by Josh Brahinsky, Jonas Mago, Mark Miller, Shaila Catherine, and Michael Lifshitz.