Children of parents with alcohol use disorders are at an increased risk of early aging and related health problems, a recent study from the Texas A&M School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences has found. The research reveals that parents who abuse alcohol can pass on symptoms of early aging to their offspring, such as high cholesterol, heart problems, arthritis, and early onset dementia, which can manifest in their children’s forties. THe findings have been published in the journal Aging and Disease.

The study, led by Michael Golding, a professor in VMBS’ Department of Veterinary Physiology and Pharmacology, aimed to explore the causes behind the early aging and disease susceptibility in children of alcohol-abusing parents. Scientists had long observed that children from these environments were more prone to sickness and had behavioral problems, but the underlying reasons remained unclear.

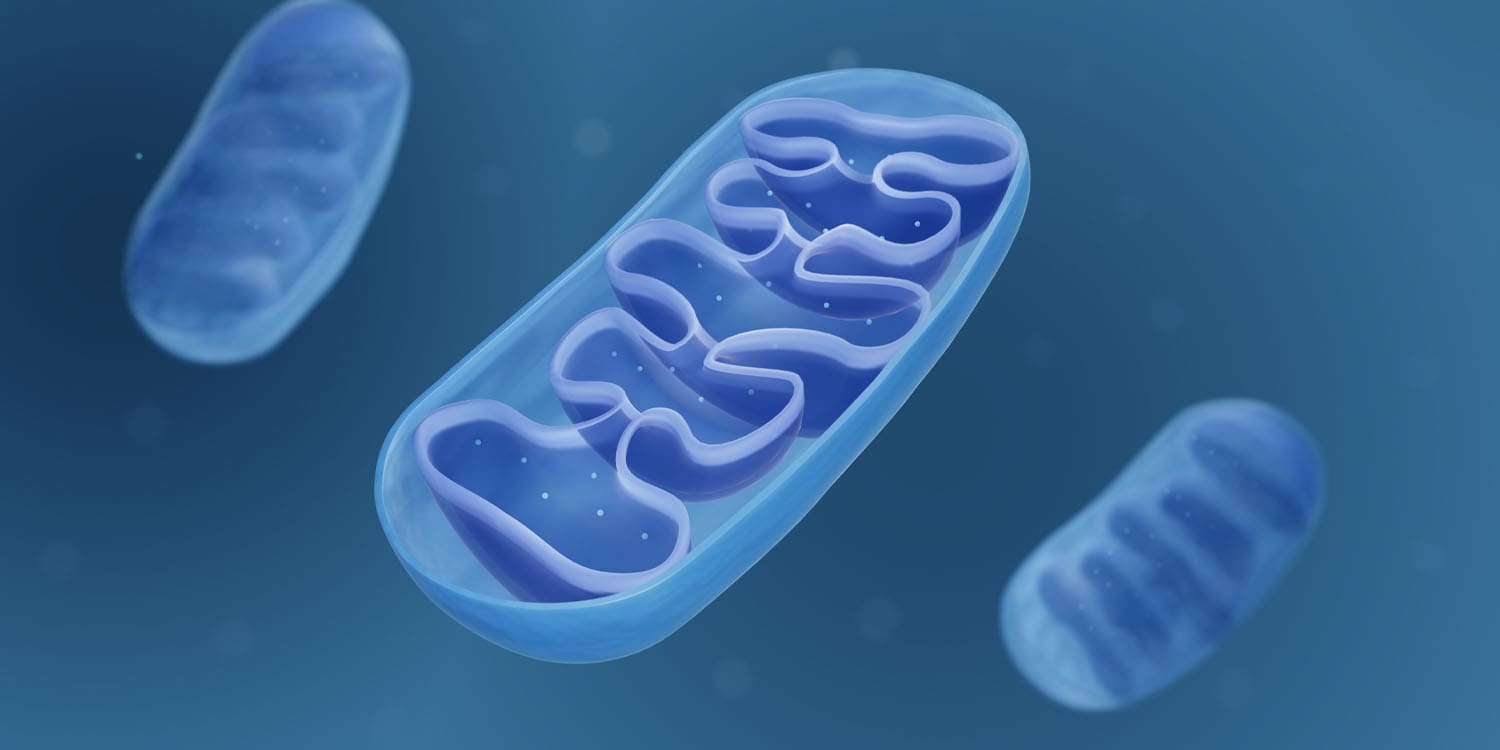

Golding and his team discovered that the dysfunction in mitochondria, the energy-producing structures within cells, was a key factor. This mitochondrial dysfunction, inherited from parents with alcohol use disorders, leads to early signs of age-related diseases in the offspring. The study’s findings highlight the importance of mitochondrial health and suggest that improving it through exercise and increased intake of certain vitamins could potentially delay these inherited dysfunctions.

The researchers utilized a mouse model to simulate the effects of parental alcohol use on offspring. Male and female mice were exposed to either a control treatment (water) or a 10% ethanol solution to mimic alcohol consumption. The exposure began when the mice reached adulthood and continued for several weeks. Females were exposed to alcohol both before conception and during the early stages of pregnancy.

The researchers then compared the offspring from different groups: control (no alcohol exposure), maternal exposure (only mothers drank alcohol), paternal exposure (only fathers drank alcohol), and dual exposure (both parents drank alcohol).

Males were exposed to alcohol for six weeks, corresponding to one full spermatogenic cycle, to ensure that any potential epigenetic changes in their sperm would be present during mating. Females were exposed to alcohol starting ten days before breeding and continuing until gestational day ten, at which point all treatments were ceased.

The offspring were then monitored for various markers of aging and mitochondrial function at different stages of their lives, culminating in a detailed analysis at 300 days old (equivalent to middle age in mice).

The researchers discovered evidence that parental alcohol consumption leads to early aging and mitochondrial dysfunction in their offspring. One of the most striking findings was the increase in cellular senescence in the brains and livers of the offspring. Cellular senescence is a state where cells cease to divide and accumulate damage, contributing to aging and age-related diseases. The study found elevated levels of senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity and increased expression of genes like p21 and p16Ink4a in the brains of the offspring, indicating accelerated aging.

“Senescence is a key marker of aging, especially in the brain, where it leads to cognitive dysfunction and memory problems,” Golding said. “Scientists have known for a long time that heavy alcohol use can cause early onset of senescence in adults.”

In the liver, male offspring showed significant markers of early liver disease, such as increased fat accumulation and fibrosis. These effects were most pronounced in offspring from the dual exposure group, where both parents had consumed alcohol, suggesting an additive effect of maternal and paternal alcohol use. Additionally, the offspring exhibited higher levels of inflammatory markers and signs of liver damage, such as increased alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase levels, even though they had never consumed alcohol themselves.

“We also see fat increase in the liver, which creates scar tissue,” Golding said. “It’s especially common in male offspring. In fact, if both parents have an issue with alcohol abuse, it can have a compounded effect on male offspring, making them even more likely to get liver disease.”

Furthermore, the study highlighted mitochondrial dysfunction as a key factor in the early aging process observed in these offspring. Mitochondrial health was assessed by examining the ratio of long to short isoforms of OPA1, a protein involved in mitochondrial dynamics. The offspring of alcohol-exposed parents, particularly those from the dual exposure group, showed a shift towards the short isoform of OPA1, indicating mitochondrial stress. This mitochondrial dysfunction was accompanied by a decrease in the NAD+/NADH ratio and reduced levels of SIRT1 and SIRT3 proteins, which are essential for maintaining mitochondrial function and preventing oxidative stress.

“Now we know that they’re inheriting dysfunction in their mitochondria as a result of their parents’ substance abuse,” Golding said. “The dysfunction causes these individuals to show early signs of age-related disease when they’re still considered young.”

The study’s findings suggest that parental alcohol use can have long-lasting and detrimental effects on the health and aging of their offspring. The results emphasize the importance of considering both maternal and paternal health before conception.

“Parental health pre-conception — both parents’ overall health before pregnancy — is critical for the health of offspring,” he explained. “The more you can do as a prospective parent to get into a healthy mindset and a healthy lifestyle, the more significant effects you’ll have on the health of your kid both right at birth and even into their 20s and 40s.”

The study, “Parental Alcohol Exposures Associate with Lasting Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Accelerated Aging in a Mouse Model,” was authored by Alison Basel, Sanat S. Bhadsavle, Katherine Z. Scaturro, Grace K. Parkey, Matthew N. Gaytan, Jai J. Patel, Kara N. Thomas, and Michael C. Golding.