A science-fiction inspired spacesuit converts astronauts’ urine into water fit to drink.

In the series Dune, a group called the Fremen live on the arid planet Arrakis. These desert dwellers recycle their bodies’ moisture using specially designed outfits called stillsuits.

“I’ve been a fan of the Dune series for as long as I can remember,” says Sofia Etlin. She studies space medicine and policy at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. For her, “building a real-life stillsuit was always a bit of a dream.”

While suited up in space, astronauts now relieve themselves into what’s known as a maximum-absorbency garment. Essentially a diaper, it can be uncomfortable, leak and cause infections.

Current spacesuit designs also contain an in-suit drinking bag, or IDB. It holds less than a liter (4.2 cups) of water. That’s not ideal for astronauts who sometimes go on strenuous 8- to 12-hour spacewalks, Etlin says. And NASA’s future missions on the moon will probably see explorers spending that long or more on the lunar surface. But Etlin says there’s no plan yet to give moonwalkers bigger IDBs.

Here’s where the new tech could really help.

Pee prepared to drink

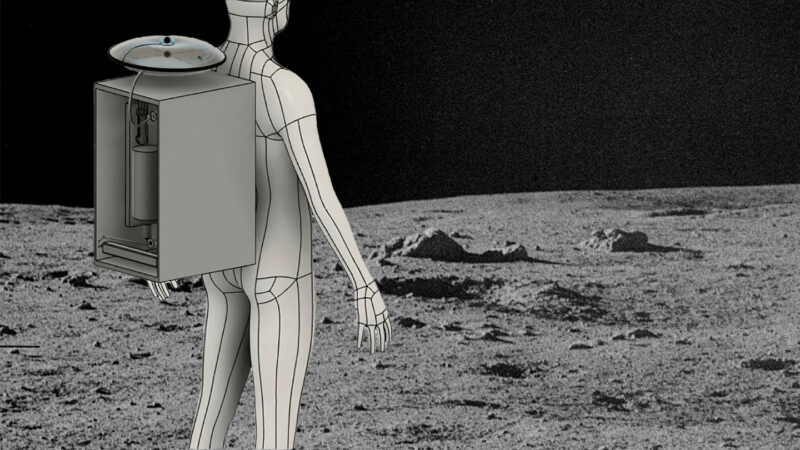

Etlin is part of a team that designed and built a new undergarment. Its collection cup covers an astronaut’s private parts. The system routes any urine into a filtering system. It removes salty water from the waste and then pumps that salt out.

The cleansed water is not yet ready to sip. Drinking water contains electrolytes — charged atoms or molecules — that our bodies need. So the newly filtered water gets a dose of those electrolytes before it’s sent into the IDB.

In Dune, body movements power a Fremen’s stillsuit. Today’s astronauts will instead carry a battery to power it. The total system, including pumps, sensors and display screen, weighs around 8 kilograms (17.6 pounds). It can purify half a liter of water (2.1 cups) in just five minutes.

The researchers shared their design July 12 in Frontiers in Space Technology.

Sweat — which fictional stillsuits also collect — would be easier to filter than urine, Etlin says. But her team focused on a single waste product for its first prototype. “One step at a time,” she says.

The team hopes to further test their system on Earth, during simulated moon and Mars missions — then someday during real spacewalks.

The spacesuit “would be amazing for us,” says Julio Rezende. He works at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte in Natal, Brazil. Rezende leads Habitat Marte. It’s a project in Brazil that imitates what it would be like for explorers to live on Mars. “I believe this technology would bring a lot of benefits,” he says.

Rezende sees spin-offs that could be helpful on Earth, too. A similar system could slake the thirst of firefighters combating remote wildfires, for instance, or hikers on long trails.