This is another in a year-long series of stories identifying how the burgeoning use of artificial intelligence is impacting our lives — and ways we can work to make those impacts as beneficial as possible.

Clues to which images are deepfakes may be found in the eyes.

Deepfakes are phony pictures created by artificial intelligence, or AI. They’re getting harder and harder to tell apart from real photos. But a new study suggests that eye reflections may offer one way to spot deepfakes. The approach relies on a technique used by astronomers to study galaxies.

Researchers shared these findings July 15. They presented the work at the Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting in Hull, England.

In real images, light reflections in the eyes match up. For instance, both eyes will reflect the same number of windows or ceiling lights. But in fake images, that’s not always the case. Eye reflections in AI-made pictures often don’t match.

Put simply: “The physics is actually incorrect,” says Kevin Pimbblet. He’s an astronomer at the University of Hull. He worked on the new research with Adejumoke Owolabi while she was a graduate student there.

Astronomers use a “Gini coefficient” — an index of how light is spread across some image of a galaxy. If one pixel has all the light, the value is 1. If the light is spread evenly across pixels, the index is 0. This measure helps astronomers sort galaxies by shape, such as spiral or elliptical.

The researchers applied this idea to photos. First, they used a computer program to detect eye reflections in pictures of people. Then, they looked at pixel values in those reflections. The pixel value represents the intensity of light at a given pixel. Those values could then be used to calculate the Gini index for the reflection in each eye.

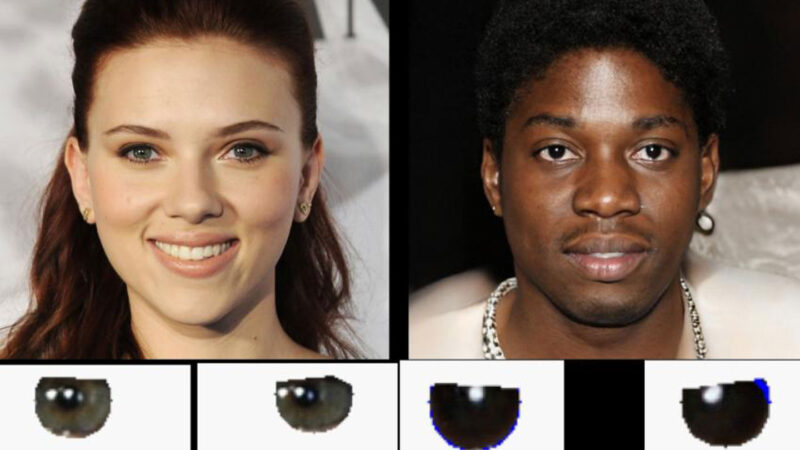

Each of these pairs of eyes (left) have reflections (highlighted on the right) that reveal them as deepfakes.Adejumoke Owolabi

The difference between the Gini coefficient of the left and right eye can hint at whether an image is real, they found. For about seven in every 10 of the fake images examined, this difference was much greater than the difference for real images. In real images, there tended to be almost no difference between the Gini index of each eye’s reflection.

“We can’t say that a particular [difference in Gini index] corresponds to fakery,” Pimbblet says. “But we can say it’s [a red flag] of there being an issue.” In that case, he says, “perhaps a human being should have a closer look.”

This technique could also work on videos. But it is no silver bullet for spotting fakes. A real image can look bogus if someone is blinking. Or if someone is so close to a light source that only one of their eyes reflects it.

Still, this method may be yet one more useful tool for weeding out deepfakes. At least, until AI learns to get reflections right.