A series of studies conducted with U.S. and Canadian children and adults examined whether people believe that their abilities would improve if they used objects owned by celebrities with related skills. The results showed that people prefer using objects that belonged to celebrities and view them as more valuable, but they generally do not believe these objects would enhance their abilities. The research was published in Cognitive Development.

People are often willing to pay large sums of money for items that once belonged to celebrities. For example, Babe Ruth’s baseball bat and John Lennon’s guitar sold at auctions for $1.9 million and $2.4 million, respectively, in recent years. This, along with many similar examples, suggests that people tend to believe objects once owned by celebrities have greater value than identical objects not associated with a famous person.

However, it remains unclear where this perception of extra value comes from. Do people believe that objects owned by celebrities confer the celebrity’s special abilities or skills to the person using them? For instance, would someone expect to become a better tennis player by using a racquet belonging to Serena Williams or Novak Đoković, as opposed to an identical racquet that was not owned by a famous tennis player or had no previous owner? Such beliefs are referred to as “ability contagion,” described as “an expected improvement in a person’s performance when using a celebrity’s object.”

Study author Kristan A. Marchak and her colleagues sought to explore people’s beliefs in ability contagion. They conducted three studies to examine judgments made by U.S. and Canadian children about objects belonging to celebrities.

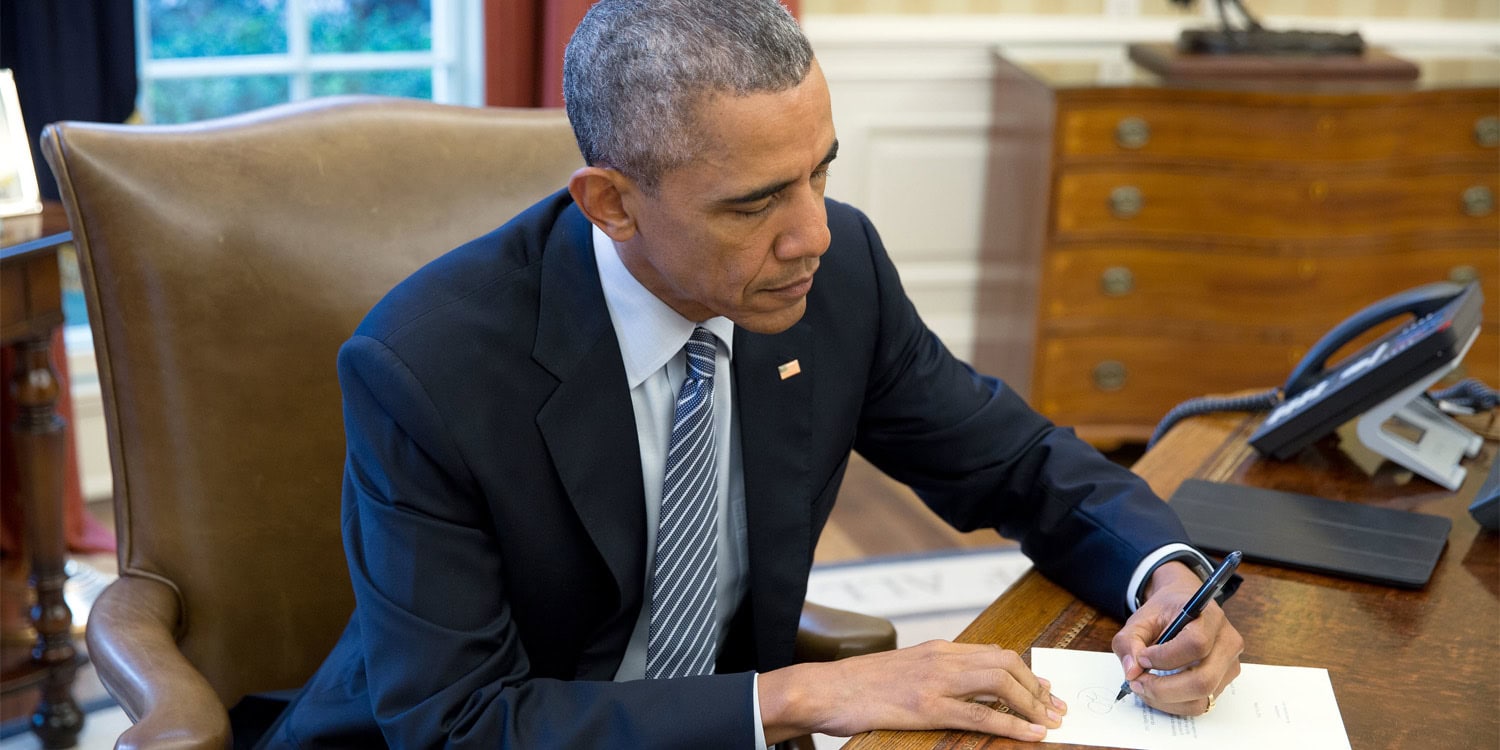

Study 1 examined whether children believed in ability contagion. Seventy 4- to 7-year-olds participated in the study at a university laboratory in the U.S. Midwest. Children played a drawing game for which they chose one of two pens. One pen was presented as belonging to President Obama, while the other was said to belong to a Mr. Smith (a non-celebrity). The study included an introduction to ensure children knew who President Obama was.

In the second stage of the game, the researchers randomly assigned the pens to children, making sure they knew whose pen they were using. The researchers then compared the children’s performance in the drawing game as an implicit measure of their belief in ability contagion. The expectation was that children would perform better with “President Obama’s pen” if they believed it would enhance their abilities.

The second study included 72 children aged 5 to 8 and 36 adults. Participants were told four stories about pairs of different objects. In each story, one object belonged to a celebrity (e.g., Taylor Swift’s guitar), and the other belonged to a non-celebrity. Participants were asked to indicate which object in each pair was worth more, which belonged in a museum, and which would help them perform better in the activity associated with the object (e.g., playing guitar).

The third study replicated Study 2, with one key difference: participants were given the option to say that the two objects they were comparing were the same. This additional option allowed the researchers to determine if participants believed the objects were truly equal in their ability to enhance performance or if they felt compelled to choose between them. Participants included 72 children aged 5 to 8 and 36 adults, the same demographic groups as in Study 2.

In Study 1, over 90% of children chose President Obama’s pen to play the game. However, there were no differences in the children’s game performance based on which pen they used. Confidence ratings also did not differ, indicating that children did not believe President Obama’s pen would make them better at the game.

In Studies 2 and 3, the responses of adults and older children suggested that they saw objects owned by celebrities as more valuable than identical objects owned by non-celebrities, and they believed these objects belonged in a museum. However, their answers did not support the idea of ability contagion. In Study 2, 99% of adults said that celebrity-owned objects were worth more and that they belonged in a museum. Children gave similar responses, although they were slightly less likely than adults to choose the celebrity object. While they occasionally said that a celebrity’s object might help them perform better, the difference was small, and they were not given the option to say both objects were the same in this study.

In Study 3, over 90% of adults again said that celebrity-owned objects were worth more and belonged in a museum more than non-celebrity-owned objects. However, when asked whether these objects would improve their abilities, they said the effects were the same. In other words, they did not believe in ability contagion. About half of the children in Study 3 believed the objects were worth the same and belonged in a museum, and around 60% said that both objects would equally help with performance. These responses indicated that neither adults nor children generally believed in ability contagion.

“The results of three studies show that children and adults do not believe that a person’s performance will improve when using a celebrity object. Our data do not support the ability contagion account of the valuation of celebrity objects and open future avenues of research to explore the qualities that children and adults expect to transfer from people to objects or vice versa,” the study authors concluded.

The study provides an intriguing exploration of ability contagion beliefs, but the authors note several limitations. One challenge was finding real-world celebrities that very young children would recognize. Most celebrities familiar to young children are fictional characters, which may not evoke the same perceptions as real-life figures. The results for the youngest children might have been different if the study had focused on celebrities more familiar to them, such as cartoon characters or figures from children’s television shows. Additionally, future studies could explore whether people’s beliefs in ability contagion might vary depending on their emotional connection to the celebrity or the type of object in question.

The paper, “Can Serena Williams’s tennis racquet make me a better tennis player? Beliefs about Ability Contagion in Children and Adults,” was authored by Kristan A. Marchak, Marianne Turgeon, Merranda McLaughlin, and Susan A. Gelman.