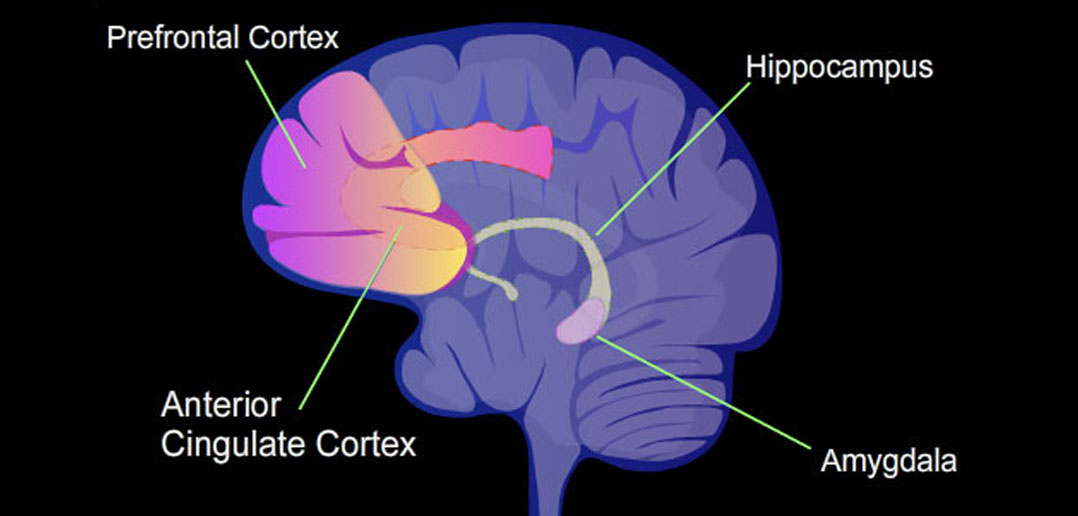

A recent replication study published in iScience has confirmed previous findings that political ideology is associated with differences in brain structure, though with some nuanced updates. The study showed that conservative voters tend to have a slightly larger amygdala than progressive voters—by approximately the size of a sesame seed. However, the researchers found no consistent link between political views and the size of the anterior cingulate cortex, which is involved in tasks like conflict monitoring and emotional regulation.

The idea that people with different political ideologies may have structural differences in their brains has been an intriguing hypothesis in political psychology for over a decade. Early studies, such as one conducted in 2011, suggested that conservatives have a larger amygdala, which might make them more responsive to fear and threat-related stimuli. In contrast, liberals were thought to have a larger anterior cingulate cortex, potentially making them better at managing uncertainty and adapting to new information.

However, these initial studies had limitations. They often relied on small, homogeneous samples—typically university students—which made it difficult to generalize the results to broader, more diverse populations. Moreover, political ideology is a complex and multifaceted concept, encompassing economic, social, and cultural dimensions that are not always captured by a simple left-right political spectrum. Recognizing these gaps, the authors of the new study sought to replicate and extend the earlier findings using a much larger and more diverse sample.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the interplay between biology and behavior, especially in the context of social and political issues,” said study author Diamantis Petropoulos Petalas, an assistant professor of psychology at The American College of Greece and member of the Hot Politics Lab at the University of Amsterdam.

“Political ideology is such a fundamental aspect of human identity, yet we know surprisingly little about its underlying mechanisms. Replicating previous findings advocating for biological correlates—like differences in brain structure—that contribute to our political beliefs is important for science, while it offers a unique perspective on why people hold different ideologies and what factors might influence these beliefs beyond upbringing or culture.”

The replication study aimed to address the limitations of earlier research by using a more robust methodology. The researchers used structural MRI scans from a large public dataset known as the Amsterdam Open MRI Collection, which includes brain imaging data from 928 healthy volunteers. This is about ten times the sample size of earlier studies, making the findings more statistically reliable. Participants were, on average, 22.86 years old, with a relatively balanced gender distribution (52% female).

Participants were asked to self-identify their political views on a seven-point Likert scale for each dimension. For social ideology, they indicated whether they saw themselves as progressive or conservative. For economic ideology, they were asked to place themselves on a left-right spectrum in terms of their beliefs about government intervention in the economy.

In addition to these self-identification measures, the researchers asked participants specific policy questions to capture their issue-based ideologies. Economic ideology was measured using four questions that asked participants about their views on income inequality, profit-sharing, and the government’s role in reducing disparities in ownership and wealth. Social ideology was assessed with questions about gender roles and attitudes toward homosexuality. .

The primary brain regions of interest in this study were the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex. These areas were chosen because of their involvement in emotional regulation and cognitive control, processes that are theoretically linked to political orientation. The researchers used voxel-based morphometry, a technique that allows for the measurement of gray matter volume in specific brain areas, to assess the size of the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex in each participant.

The study successfully replicated a key finding from earlier research: on average, conservative participants had larger amygdalas compared to their more progressive counterparts. Although the size difference was small, it was statistically significant, suggesting that conservatives may be more sensitive to fear or threat-related stimuli—a role the amygdala is known to play in emotional processing.

Interestingly, the relationship between amygdala size and conservatism was specific to social conservatism and did not extend to economic conservatism. For example, individuals who supported the Socialist Party, which advocates for radically left-wing economic policies but holds more conservative social values, had larger amygdalas on average compared to those aligned with other progressive parties.

“What surprised us most was the consistency of the amygdala-conservatism link, even in a multiparty political system like the Netherlands,” Petropoulos told PsyPost.

However, the researchers did not find consistent evidence that liberals had a larger anterior cingulate cortex, which contradicts some earlier studies. While this region was hypothesized to be larger in progressives due to its role in conflict monitoring and adaptability, the current study did not find a reliable link between its size and political ideology.

The researchers also conducted whole-brain analyses to see if other brain regions, beyond the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex, were related to political ideology. They found a positive relationship between social conservatism and gray matter volume in the right fusiform gyrus, a brain region involved in visual processing and social perception. This suggests that other brain areas, beyond the traditional focus on the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex, may also be involved in shaping political views.

“We did not expect to find an association between conservatism and the fusiform gyrus, which adds a new dimension to our understanding of how ideology may relate to social information processing,” Petropoulos said.

The fusiform gyrus has been linked to processes like face recognition and the perception of social categories, such as race and gender. The researchers speculate that structural differences in this area may reflect how individuals process social information, which could be related to their political ideology.

“The main takeaway is that our political beliefs may be shaped not only by our environment and experiences but also by our biology,” Petropoulos explained. “We found that certain brain structures, like the amygdala and fusiform gyrus, are associated with political ideology. While this doesn’t mean our brains ‘determine’ our political views, it suggests that biology plays a role in how we perceive and react to the world, influencing our political preferences.”

Although the researchers found that political ideology is associated with differences in brain structure, they cannot say whether these brain differences cause people to hold certain political views, or if holding certain views over time might influence brain development. Longitudinal studies that track brain changes and political beliefs over time would be needed to clarify this relationship.

In addition, while the sample was larger and more diverse than in previous studies, it was still primarily drawn from the Netherlands, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other political systems. For example, in a country like the United States with a more polarized two-party system, the relationships between brain structure and political ideology might differ.

“While our study used a large and representative sample, it is still only one piece of the puzzle,” Petropoulos told PsyPost. “In the long term, I hope to explore how these brain-ideology associations change over time and whether environmental factors, such as political events or life experiences, or certain genotype can alter brain structures or functions related to ideology. I am also interested in examining functional brain connectivity to understand how different regions interact when processing political information.”

“I think it’s important for people to understand that our findings should not be used to reinforce stereotypes or suggest that political beliefs are fixed. The brain is incredibly adaptable, and political beliefs are shaped by many factors. Instead, understanding the biological influences on ideology may help us appreciate the diversity of perspectives and improve our ability to communicate across ideological divides.”

The study, “Is political ideology correlated with brain structure? A preregistered replication,” was authored by Diamantis Petropoulos Petalas, Gijs Schumacher, and Steven H. Scholte.