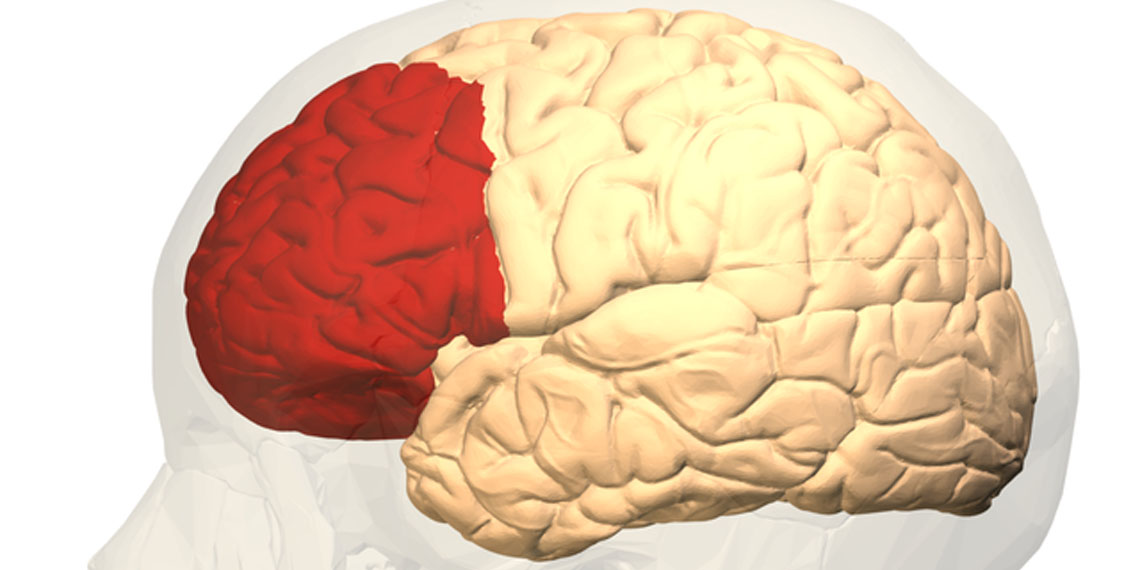

A recent study by researchers from Waseda University offers promising insights into the effects of light-intensity exercise on children’s brain function. The research, published in Scientific Reports, found that even short bursts of simple exercises can increase blood flow to the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for important cognitive functions like decision-making, memory, and attention. This discovery could pave the way for easy-to-implement exercise routines that improve brain function, particularly in children, who often lead increasingly sedentary lifestyles.

Physical activity is known to enhance cognitive function, but most of the existing research has focused on moderate-to-vigorous forms of exercise, such as running or sports. These forms of exercise are known to improve brain function by increasing blood flow and promoting the growth of new neurons. However, many children around the world do not engage in enough physical activity, and sedentary behavior is on the rise. In fact, 81% of children globally do not meet the recommended levels of physical activity, which raises concerns about their brain development and cognitive function.

“Sedentary lifestyles and physical inactivity are prevalent among children worldwide,” said study author Takashi Naito, a doctoral student at Waseda University and visiting researcher at the Waseda Institute of Human Performance. “We aim to develop an exercise program that can be easily performed in the homeroom or between school classes to prevent sedentary behavior in children and positively affect their brains. Even light-intensity physical activity has health benefits. As the first step, we examined the effects of light-intensity exercise on cerebral blood flow.”

The study involved 41 healthy children, ranging from fifth graders to junior high school students in Japan. The researchers introduced the children to seven different types of light-intensity exercises. These exercises were chosen because they could be easily performed without special equipment and required minimal movement of the head and body, which helped reduce noise in the brain activity measurements.

The exercises included movements such as:

Upward Stretch (reaching upward with folded hands)

Shoulder Stretch (stretching one arm across the chest)

Elbow Circles (rotating elbows widely)

Trunk Twist (twisting the upper body)

Washing Hands (rubbing hands together)

Thumb and Pinky (a finger dexterity exercise)

Single-leg Balance (standing on one leg for balance)

Most of these exercises were performed while seated, except for the balance exercise. The children performed each exercise for either 10 or 20 seconds, and the researchers measured their brain activity during the exercises using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). This technology tracks changes in blood flow by measuring concentrations of oxygenated hemoglobin in the prefrontal cortex.

The study revealed that all forms of exercise, except for some static stretches, significantly increased blood flow to the prefrontal cortex compared to the resting state. This increased blood flow is a sign of heightened brain activity, particularly in regions associated with executive functions such as working memory, attention, and decision-making.

“I was surprised that rubbing hands and moving fingers for 10 to 20 seconds increased blood flow to a certain extent in the prefrontal cortex,” Naito told PsyPost. “Since the hands have a strong connection with the brain, I expected the cerebral blood flow to increase slightly; however, the results were better than expected.”

Interestingly, the exercises that involved more movement or a higher cognitive load, such as twisting the trunk or balancing on one leg, led to the greatest increases in brain activity. For example, exercises like elbow circles, which required broader movements, and single-leg balance, which required concentration to maintain balance, showed notable increases in blood flow in multiple regions of the prefrontal cortex.

“One-leg balance is a simple exercise,” Naito said. “Still, I was surprised it increased the blood flow to the prefrontal cortex to such an extent.”

In contrast, simpler static exercises, such as the shoulder stretch, showed minimal changes in brain activity. This suggests that the more demanding the exercise, either physically or mentally, the more it stimulates the brain.

Additionally, the researchers found no significant difference in the brain activity increases between exercises performed for 10 seconds versus those performed for 20 seconds. This suggests that even very short bursts of light-intensity exercise are sufficient to boost brain function.

The findings provide evidence that “even short-duration, light-intensity exercise can create changes in the body that may improve body and brain health compared to staying in the same position for long periods,” Naito explained. “Even if you are working, studying, or watching TV at a desk, move your body a little now and then.”

While the results are promising, the study has some limitations. First, the age range of the participants was relatively narrow, focusing on children between 10 and 15 years old. Further research is needed to see if similar results would be observed in younger children, older adolescents, or adults. Moreover, the study did not account for factors like the children’s individual physical fitness, daily activity levels, or body mass index, all of which could influence the results.

Another limitation is that while the study measured increases in blood flow to the prefrontal cortex, it did not directly test whether this increased blood flow translated into improved cognitive performance.

“This study showed that short-duration, light-intensity exercise increased cerebral blood flow in the prefrontal cortex, except for monotonous movement stretching,” Naito said. “However, further research is needed to determine whether this leads to improved cognitive function; we are currently conducting this verification.”

The researchers are optimistic that light-intensity exercises could become a regular part of school routines, helping to combat the negative effects of sedentary behavior while promoting cognitive development.

“Based on the findings of this study, we are now developing a light-intensity exercise program lasting a few minutes and examining whether it positively affects not only cerebral blood flow but also children’s cognitive functions,” Naito explained. “We plan to promote our research so that many schools will implement the program, which anyone can easily perform, to prevent sedentary behavior in children and to improve cognitive functions. We would also like to expand these programs for adults and older people to maintain and improve cognitive function.”

The study, “Hemodynamics of short-duration light-intensity physical exercise in the prefrontal cortex of children: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study,” was authored by Takashi Naito, Koichiro Oka, and Kaori Ishii.