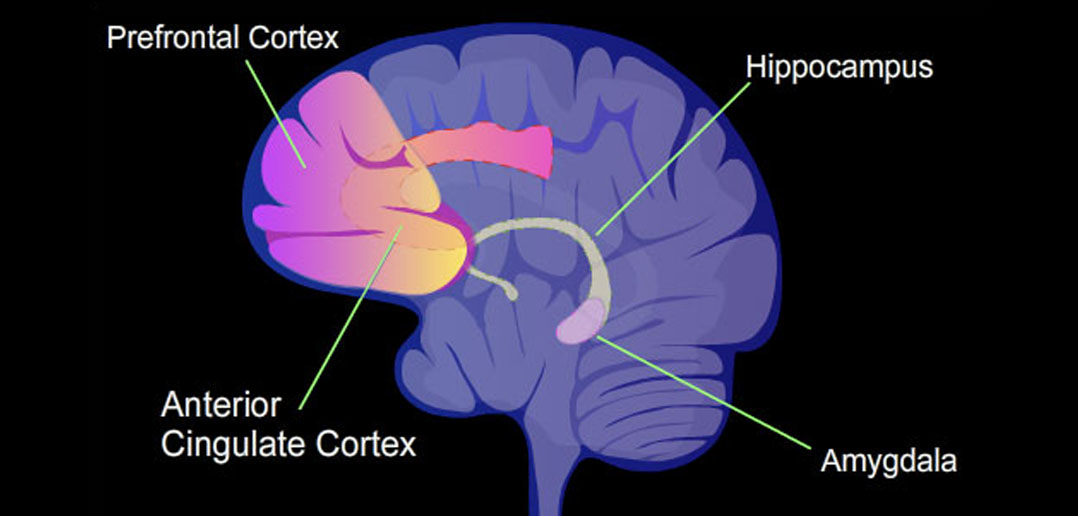

A new study published in Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging sheds light on the brain connections linked to withdrawn and depressive behaviors in children. By analyzing brain scans of over 6,000 children, researchers found that connections between the left amygdala, a part of the brain that processes emotions, and other brain regions were associated with these internalizing behaviors.

Childhood is a critical time for understanding the early markers of mental health issues. Many psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression, often begin in childhood or adolescence and can persist into adulthood if not identified and treated early. Internalizing behaviors, like withdrawal and depression, are forms of distress that manifest inwardly, making them more challenging to detect than outwardly directed behaviors such as aggression. These behaviors can also indicate a higher risk of developing mental health disorders later in life.

Previous research has suggested that the amygdala, a brain region known for its role in processing emotions, plays a role in anxiety and depression. However, many prior studies had small sample sizes, limiting the reliability of the findings. The new study, using data from the large-scale Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, aimed to clarify the connections between the amygdala and other brain regions in a large, diverse population of children, providing more generalizable results.

“I have always been interested in identifying ways to improve the diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses. My interest in internalizing behavior stems from my behaviors—I always say ‘research is me-search,’” said study author Elina Thomas, an assistant professor of neuroscience at Earlham College.

The researchers used data from the ABCD study, which tracks the development of thousands of children across the United States. For their study, they analyzed brain scans and behavioral reports from 6,371 children aged 9 to 10 years old. The brain scans used a technique called resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow. The researchers focused specifically on the connections between the left and right amygdala and other brain regions, examining how these connections might be linked to different internalizing behaviors.

Parents provided information on their child’s behaviors using a standardized questionnaire, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), which measures internalizing behaviors like depression, anxiety, and withdrawal. The researchers also gathered additional data on factors that might influence these behaviors, including whether the children had experienced traumatic events, their genetic predisposition to depression, and demographic information such as age, sex, and parental education.

The researchers did not find significant associations between overall internalizing behavior (a broader category that includes anxiety, depression, and somatic complaints) and amygdala connectivity. This suggests that specific components of internalizing behavior may have distinct brain correlates, rather than all internalizing behaviors being linked to the same brain networks.

“I was surprised that we did not see associations between amygdala connectivity and internalizing symptoms overall, as this has been shown many times in the literature,” Thomas told PsyPost. “I suspect this is due to the small sample sizes typically used to examine these associations.”

When examining specific components of internalizing behavior, the researchers observed that stronger connections between the left amygdala and regions involved in attention and social behaviors—such as the dorsal attention network and the frontoparietal network—were linked to higher levels of social anxiety, social impairment, and social problems. These networks are responsible for maintaining attention and helping the brain process sensory information from the world, making them important for how individuals interact with others.

Interestingly, stronger connections between the left amygdala and the dorsal attention network were associated with more severe social anxiety, while connections with the frontoparietal network were linked to greater social impairment. On the other hand, a connection between the amygdala and an auditory processing area was related to fewer social problems. These findings suggest that the way the amygdala communicates with different parts of the brain may influence how children experience and navigate social situations, particularly when they are feeling anxious or withdrawn.

“Mental illness is not binary,” Thomas explained. “That is to say, typically, an individual does not fit entirely into the box of one mental illness. Symptoms exist on a spectrum and should be measured accordingly. One way to do this is by looking at different subcomponents that make up a typical behavior. Our study shows that the subcomponents associated with internalizing behavior are more closely linked to the brain than the overall construct, suggesting future studies should look at these different components separately.”

While this study provides valuable insights into the brain networks associated with internalizing behaviors in children, it also has some limitations. First, the study only looked at a single snapshot in time, meaning that it cannot show how these brain connections and behaviors change as children grow older. The authors suggest that future research should explore how these brain networks develop over time, especially as many mental health issues become more pronounced in adolescence. A longitudinal approach could help determine whether these brain connections are stable markers of mental health risk or if they change as children mature.

Additionally, while the study found significant associations between certain amygdala connections and social behaviors, the effect sizes were relatively small. This is not uncommon in large studies, as small effects can still be meaningful when studying complex behaviors like depression and anxiety. Nonetheless, it suggests that these brain connections are likely only part of the puzzle when it comes to understanding internalizing behaviors in children.

“Our sample was made up of children with low levels of internalizing behavior because it was a healthy sample; we might have seen different associations in a sample with higher internalizing behaviors, or diagnosed anxiety or depression,” Thomas said.

“My lab is currently examining environmental factors that might impact amygdala connectivity, particularly perceived discrimination. We have already found a significant connection between perceived discrimination and internalizing behavior, suggesting one may lead to the other.”

The study, “Amygdala connectivity is associated with withdrawn/depressed behavior in a large sample of children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study,” was authored by Elina Thomas, Anthony Juliano, Max Owens, Renata B. Cupertino, Scott Mackey, Robert Hermosillo, Oscar Miranda-Dominguez, Greg Conan, Moosa Ahmed, Damien A. Fair, Alice M. Graham, Nicholas J. Goode, Uapingena P. Kandjoze, Alexi Potter, Hugh Garavan, and Matthew D. Albaugh.