A study conducted in Hungary found that adolescents with a smaller volume in the amygdala region of the brain have a higher risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They also tend to experience more severe symptoms of this disorder. The research was published in Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology.

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by symptoms such as inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, which are severe enough to interfere with daily functioning. People with ADHD often have difficulty focusing on tasks, organizing activities, and following through with instructions. Hyperactive behaviors may include excessive fidgeting, talking, or an inability to stay seated when expected, particularly during class in school.

The disorder is most commonly diagnosed in childhood, especially at the start of primary school. However, in 65% of affected individuals, symptoms persist into adulthood with sufficient severity to cause impairments. Overall, ADHD affects 5%-9% of children and adolescents worldwide.

The causes of ADHD are not fully understood. Some studies suggest that alterations in the structure and function of certain brain areas may be involved in the disorder. Previous research has reported differences in brain volume between adults and children with and without ADHD.

Study author Ádám Nárai and his colleagues aimed to examine whether atypical brain region volumes predict the risk of ADHD and the severity of its symptoms, such as inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. If this were the case, medical professionals could compare the volumes of specific brain regions in their patients to standard brain charts, potentially identifying individuals at an increased risk of developing ADHD.

The researchers analyzed data from the Budapest Longitudinal Study of ADHD and Externalizing Disorder, a larger longitudinal project. The study included 140 adolescents, selected to overrepresent individuals with ADHD, meaning they comprised a larger share of participants than in the general population. The average age of the participants was 16 years, with 38% being female. The socioeconomic status of their families was above average. Twelve participants were taking ADHD medication at the time of the study.

Study participants underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). They also completed an assessment of anxiety and depressive symptoms using the Youth Self-Report. Their parents completed assessments of their ADHD symptoms with the ADHD Rating Scale-5 and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms using the Disruptive Behaviors Disorders-Rating Scale.

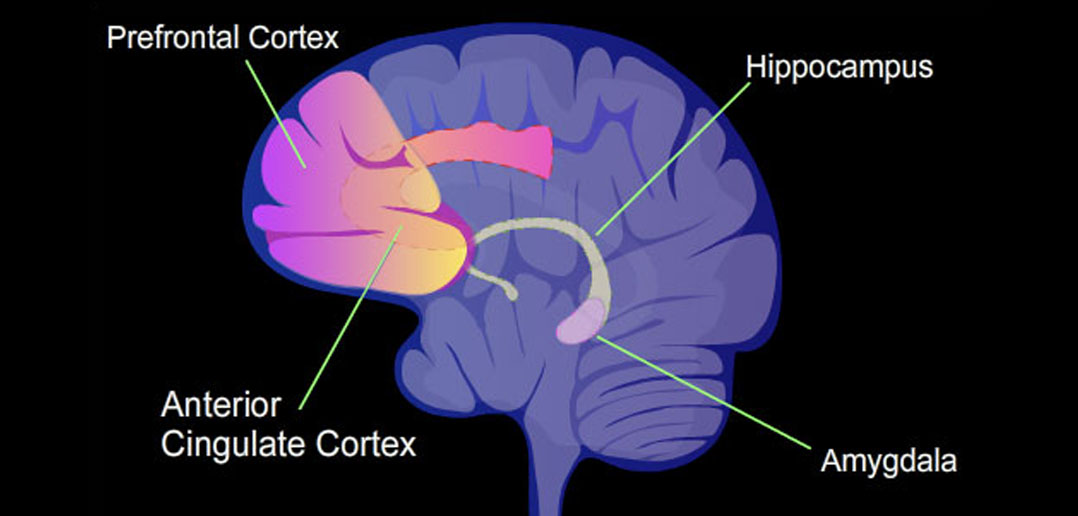

The results showed that participants with more severe oppositional defiant disorder symptoms were more likely to be at risk for ADHD. Participants with smaller volumes of subcortical gray matter were at a higher risk for ADHD. Subcortical gray matter refers to the volume of neuronal cell bodies in regions of the brain located beneath the cerebral cortex. The thickness of the cortex was not associated with ADHD risk.

Further analyses revealed that individuals with a smaller volume of the amygdala region in both brain hemispheres tended to have a higher risk of ADHD and more severe symptoms. In other words, they tended to show higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity.

The amygdalae are small, almond-shaped clusters of neurons located deep within the temporal lobes of the brain. They play a crucial role in processing emotions, particularly fear and pleasure, and are involved in forming and storing emotional memories.

“Individual differences in amygdala volume meaningfully add to estimating ADHD risk and severity. Conceptually, amygdalar involvement is consistent with behavioral and functional imaging data on atypical reinforcement sensitivity as a marker of ADHD-related risk. Methodologically, results show that brain chart reference standards can be applied to address clinically informative, focused and specific questions,” the study authors concluded.

The study sheds light on the association between amygdala volume and the risk of ADHD. However, the study could not disentangle ADHD from oppositional defiant disorder symptoms, a condition that often co-occurs with ADHD. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the specific brain structure differences reported are specific to ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, or common to both disorders.

The paper, “Amygdala Volume is Associated with ADHD Risk and Severity Beyond Comorbidities in Adolescents: Clinical Testing of Brain Chart Reference Standards,” was authored by Ádám Nárai, Petra Hermann, Alexandra Rádosi, Pál Vakli, Béla Weiss, János M. Réthelyi, Nóra Bunford, and Zoltán Vidnyánszky.