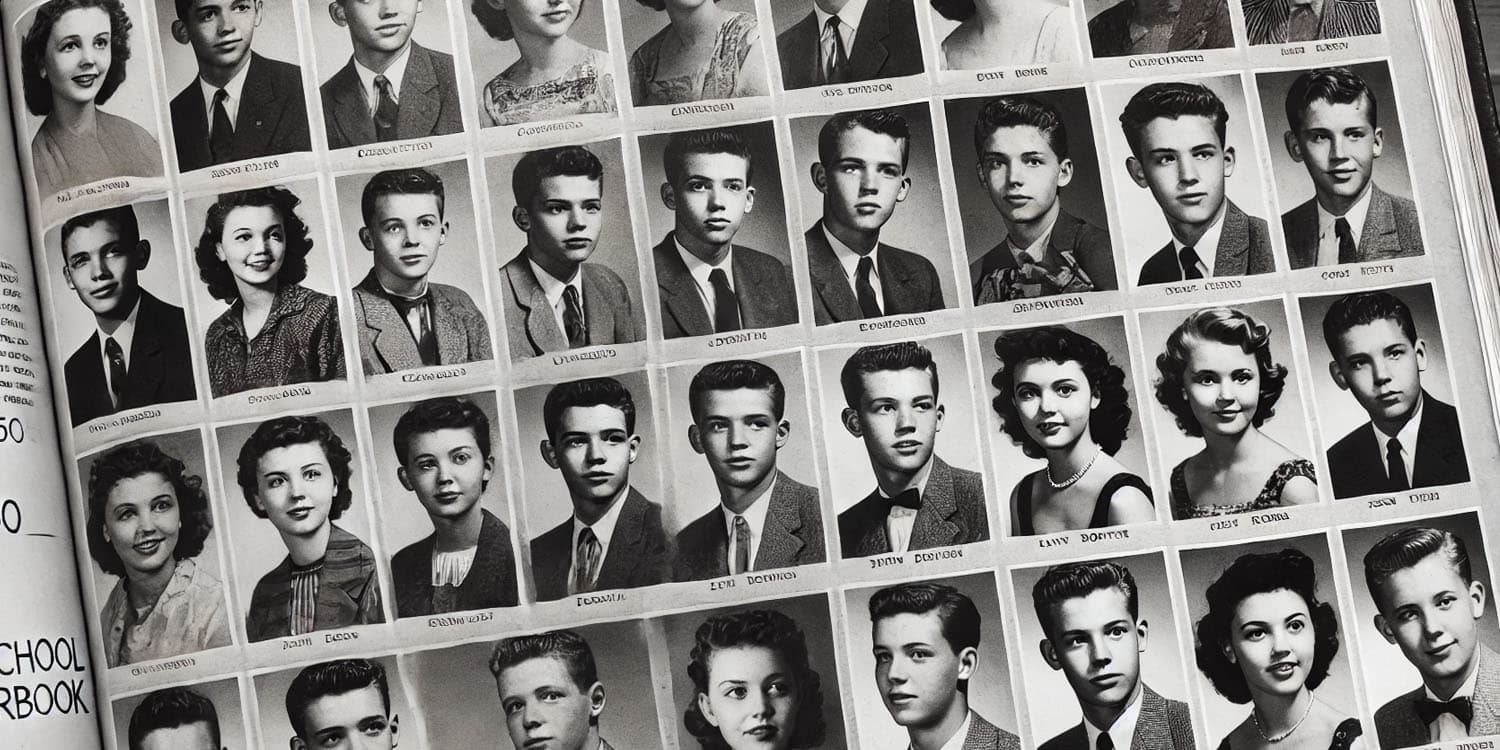

It turns out that looking good in your high school yearbook might have more significance than just reminiscing over youthful days. A new study published in Social Science & Medicine has found that people who were rated as the least attractive based on their high school yearbook photos tend to have shorter lives than their more attractive counterparts. In particular, those in the lowest attractiveness sextile had significantly higher mortality rates.

The rationale behind this study is rooted in the well-documented observation that various social conditions, such as income, marital status, and education, significantly impact health and longevity. However, the role of physical attractiveness in determining lifespan has been relatively overlooked. This oversight is noteworthy because attractiveness may not only indicate underlying health but also systematically influence critical social stratification processes that affect health outcomes.

For example, greater physical attractiveness can positively impact social stratification processes such as securing employment, earning higher incomes, and forming beneficial social connections. These social advantages can lead to better life outcomes, underscoring the significant role that societal perceptions of beauty play in shaping overall health and longevity.

Previous studies on the relationship between attractiveness and health have produced mixed results, and it remains unclear whether greater attractiveness confers a longevity advantage or if lesser attractiveness results in a penalty. Additionally, these studies often failed to account for various life-stage factors and demographic characteristics that might influence this relationship. By using a large, longitudinal dataset — the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study — the researchers sought to provide a more robust analysis.

“I have always thought that attraction is an understudied aspect of social inequality. It may not be as structural as other dimensions but everyone knows that it is important. I also met and pitched this idea to one of the foremost experts, Dr. Hamermesh, who has studied how attraction shapes the life course for decades,” said study author Connor M. Sheehan, an associate professor at Arizona State University.

The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) is a survey that followed Wisconsin high school graduates from 1957 throughout their lives. This dataset includes a sample of 8,386 individuals who were tracked until their death or through their early 80s. The researchers used high school yearbook photographs to measure facial attractiveness, which was rated by independent judges. Each respondent’s attractiveness was rated on an eleven-point scale by six male and six female raters who were trained to ensure consistency in their evaluations.

To link attractiveness with longevity, the researchers used mortality data from the National Death Index-plus, covering deaths up until 2022. They employed Cox proportional hazard models and life-table techniques to analyze the relationship between attractiveness and mortality risk.

These models allowed the researchers to account for various covariates, such as high school achievement, intelligence, family background, adult earnings, and mental and physical health in middle adulthood. By including these factors, the researchers aimed to isolate the specific impact of attractiveness on longevity.

The study found that individuals rated as the least attractive, comprising the bottom one-sixth of the attractiveness scale, had significantly higher mortality risks compared to those with average attractiveness. Specifically, those in the lowest sextile faced a 16.8% higher hazard of mortality than those in the middle four sextiles.

Interestingly, the study did not find significant differences in mortality risk between highly attractive individuals and those with average attractiveness. This indicates that while being unattractive is associated with a shorter lifespan, being highly attractive does not confer additional longevity benefits over being average-looking. This pattern was consistent across different life stages and specifications of attractiveness, reinforcing the validity of the results.

“People who were rated as the least attractive based on their yearbook photos live shorter lives than others,” Sheehan told PsyPost. “Also, and interestingly, we found no real advantage of the most attractive rated people compared to everyone else something which surprised both of us. That is, it is really more of an unattractive penalty more so than an attractiveness advantage, at least for longevity in this cohort of Wisconsin high school graduates. These findings really stress more equitable treatment of people, regardless of their looks.”

Despite the comprehensive nature of this study, it does have its limitations. One such limitation is that the sample consisted only of high school graduates from Wisconsin, which may not be representative of the entire U.S. population. The sample was also predominantly non-Hispanic White, which limits the generalizability of the findings across different racial and ethnic groups.

Another limitation is the potential variability in photograph quality and other unmeasured factors such as childhood health status, which could have influenced the attractiveness ratings and subsequent mortality risks. However, the study did control for a wide range of variables, and the findings remained consistent.

Future research should consider replicating this study with more diverse samples to understand better the intersectional processes at play, such as the impact of racialized and gendered conceptions of beauty. It would also be valuable to explore the specific pathways through which unattractiveness may lead to higher mortality risk, including potential discrimination, social stigma, and stressors faced by less attractive individuals.

The study, “Looks and longevity: Do prettier people live longer?“, was authored by Connor M. Sheehan and Daniel S. Hamermesh.