A recent study published in Neurology explored whether high doses of nicotinamide, a derivative of vitamin B3, could reduce a protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease progression. Despite promising results in animal models, the study found no significant reduction in the tau protein among participants with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease who were treated with nicotinamide for 48 weeks. The findings suggest that while the treatment appeared safe, it did not achieve its intended biological effect.

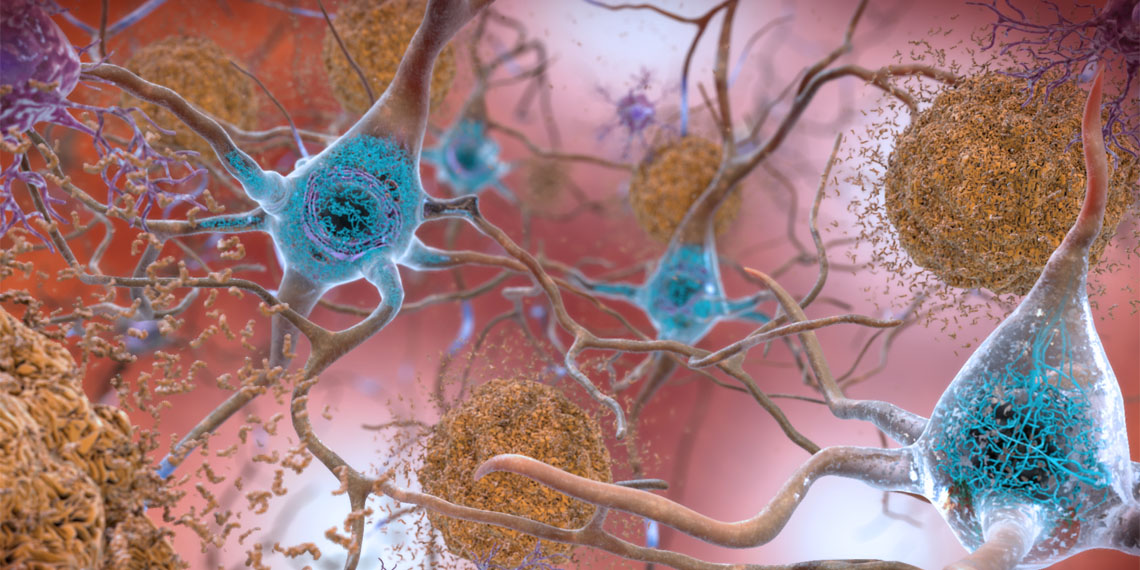

Alzheimer’s disease, a condition characterized by progressive memory loss and cognitive decline, has proven difficult to treat. Recent advancements in therapies targeting amyloid plaques, a hallmark of the disease, have been groundbreaking but come with challenges. These treatments are costly, involve intravenous administration, and carry risks of adverse effects. Researchers are seeking alternative or complementary treatments that could be safer, more accessible, and potentially target other aspects of Alzheimer’s pathology.

One such target is tau, a protein that forms tangles in the brain. Tau tangles are closely linked to disease progression and serve as a key criterion for diagnosing Alzheimer’s. Nicotinamide emerged as a candidate for investigation based on its potential to modify tau proteins. Animal studies had suggested that nicotinamide could reduce tau phosphorylation, improve cognitive function, and stabilize cellular structures in the brain. The researchers aimed to determine whether similar effects could be observed in humans with early-stage Alzheimer’s.

“The study was conducted in an effort to translate promising results in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease into human,” said study author Joshua Grill, a professor and co-director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of California, Irvine. “In a discovery made here at UC Irvine and replicated in a lab at the National Institute on Aging, nicotinamide counteracted the neurofibrillary tangles of disease in mice.”

“Additionally, it would be ideal if we could discover treatments that are cheap and easy to administer (e.g., oral therapies) that can counteract the biology of Alzheimer’s disease and this trial tested a hypothesis that oral nicotinamide could counteract the neurofibrillary tangles of the disease in mild stage patients.”

The researchers conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted over 48 weeks. It involved 47 participants who were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, as confirmed by cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Participants were recruited from two sites, the University of California, Irvine, and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either 1,500 milligrams of nicotinamide twice daily (a total of 3 grams per day) or a placebo. The treatment was administered in the form of sustained-release tablets. To ensure safety, participants underwent regular medical evaluations, including blood tests, cognitive assessments, and lumbar punctures to measure levels of tau and other biomarkers.

The primary focus of the study was to assess changes in phosphorylated tau (specifically at site 231, referred to as p-tau231) in the cerebrospinal fluid, a marker of tau modification. Secondary outcomes included other forms of tau, amyloid proteins, and measures of cognitive and functional decline.

The trial faced significant logistical challenges, including disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to delays and adjustments in data collection. Despite these hurdles, 41 participants completed the trial.

The study did not find significant differences in the levels of p-tau231 between the nicotinamide and placebo groups. While the placebo group showed a slight increase in p-tau231 levels over the course of the study, the reduction observed in the nicotinamide group was minimal and not statistically meaningful.

Other tau biomarkers, including total tau and another phosphorylated form (p-tau181), showed no significant changes attributable to nicotinamide treatment. Both groups experienced decreases in amyloid protein levels, but these changes were likely unrelated to the treatment.

Interestingly, participants in the nicotinamide group showed less decline in a clinical measure of dementia severity, the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes. However, this result did not hold up after accounting for statistical adjustments, and no similar improvements were observed in other cognitive or functional tests.

“We used the gold standard approach for testing medications—a double blind randomized placebo controlled trial,” Grill told PsyPost. “We also used biomarkers in the cerebrospinal fluid as the primary outcome. This isn’t easy, but it helps us answer questions with smaller sample sizes than studies that look at clinical and cognitive testing outcomes. Unfortunately, a relatively high dose of nicotinamide (3 g/day) was not able counteract the tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles in people with early stage Alzheimer’s disease.”

The treatment appeared safe overall, with no significant differences in the frequency or severity of adverse events between the nicotinamide and placebo groups. Most reported side effects, such as gastrointestinal discomfort and mild infections, were consistent with those seen in similar trials.

The researchers acknowledged several limitations. “The study was relatively small and only tested one dose and one duration of treatment (12 months). We don’t have reason to expect that higher dose or longer duration of treatment would make a difference, but the study didn’t address those possibilities,” Grill noted.

The study also did not include more advanced imaging techniques, such as tau positron emission tomography, which could provide deeper insights into how nicotinamide affects tau deposition in the brain. Furthermore, the disruptions caused by the pandemic likely impacted participant adherence and the consistency of data collection.

Another unanswered question is whether nicotinamide can effectively cross the blood-brain barrier in humans. Some studies suggest that nicotinamide metabolites can reach the brain, but this trial did not directly measure these metabolites.

“We are further exploring the data from the trial to see if there is reason to continue studying nicotinamide in this population,” Grill said.

The study, “Phase 2A Proof-of-Concept Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Nicotinamide in Early Alzheimer Disease,” was authored by Joshua D. Grill, Steven Tam, Gaby Thai, Beatriz Vides, Aimee L. Pierce, Kim Green, Daniel L. Gillen, Edmond Teng, Sarah Kremen, Maryam Beigi, Robert A. Rissman, Gabriel C. L´eger, Archana Balasubramanian, Carolyn Revta, Rosemary Morrison, Robin Jennings, Judy Pa, Jing Zhang, Shelia Jin, Karen Messer, and Howard H. Feldman.