A recent study published in The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine has found that patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have significantly smaller pineal glands compared to healthy individuals. This finding suggests a possible link between the pineal gland and the underlying mechanisms of OCD.

OCD is a mental health condition characterized by persistent, unwanted thoughts or urges (obsessions) that lead to repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions). People with OCD often engage in these behaviors in an attempt to reduce anxiety or prevent a feared event, but the relief is usually temporary, leading to a cycle of obsessive thoughts and compulsive actions. OCD affects about 1-2% of the population, and while its exact causes are not fully understood, research suggests a combination of genetic, environmental, and neurobiological factors contribute to its development.

“The study was motivated by the recognition that obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is associated with several neurobiological factors, yet its underlying mechanisms remain largely elusive,” said study author Muhammed Fatih Tabara, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Firat University.

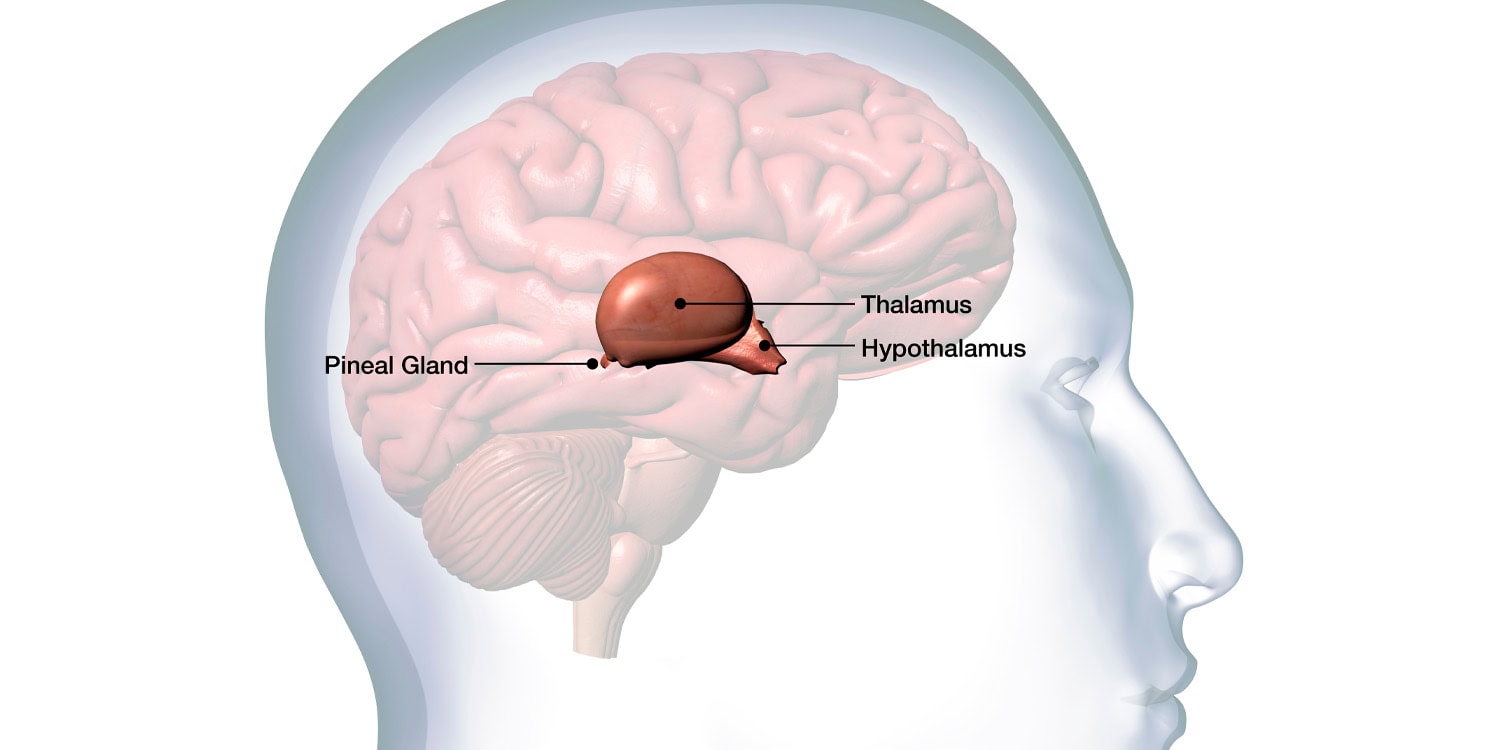

“Specifically, the pineal gland, which plays a role in regulating circadian rhythms and melatonin secretion, has not been thoroughly studied in relation to OCD. Prior research indicated hormonal alterations in conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder, and suggested a potential link between melatonin-related disruptions and OCD. However, there had been no structural studies focusing on the pineal gland in patients with OCD.”

“Given the hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, elevated levels of cortisol, and altered melatonin secretion observed in OCD, it seemed plausible that changes in pineal gland volume might be involved in the pathophysiology of the disorder. This gap in the literature sparked an interest in examining whether pineal gland volumes in OCD patients differ from those in healthy controls, which might provide insight into the disorder’s biological underpinnings.”

To conduct the study, Tabara and his colleagues recruited 20 patients diagnosed with OCD from Firat University’s psychiatry department and 20 healthy control participants. All participants were aged between 18 and 65 and met specific inclusion criteria. The patients were diagnosed with OCD based on the criteria outlined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

The researchers ensured that none of the patients had other significant psychiatric conditions, a history of severe head trauma, or medical conditions that could affect the brain’s structure. Similarly, the control group consisted of individuals without psychiatric disorders or brain abnormalities. Both groups underwent high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans using a 1.5-tesla system to capture detailed images of the brain, with a particular focus on the pineal gland.

To measure pineal gland volumes, the researchers used a semi-automated software tool that allowed them to define the boundaries of the gland with precision. A neuroradiologist who was unaware of the participants’ diagnoses conducted the measurements to minimize bias. After collecting the data, the researchers used statistical analyses to compare the pineal gland volumes between the OCD patients and the healthy controls.

The results showed a statistically significant difference in pineal gland volumes between the two groups. On average, the pineal glands of OCD patients were smaller (84.65 mm³) compared to those of the healthy control group (106.30 mm³). This finding was not influenced by demographic factors like age or gender, as these variables were evenly distributed across both groups.

Interestingly, the researchers found no significant differences in overall brain volumes or in gray and white matter between the two groups. This suggests that the reduction in pineal gland size is not part of a broader change in brain structure, but may instead be specific to the gland itself.

“The fact that the pineal gland volumes were notably smaller in the OCD group, despite no significant differences in overall brain, white matter, or gray matter volumes, was unexpected,” Tabara told PsyPost.

These findings point to a potential connection between OCD and the pineal gland, particularly given the gland’s role in regulating circadian rhythms and melatonin production. Previous research has shown that people with OCD often experience sleep disturbances and altered levels of hormones like cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), both of which are related to stress and the body’s circadian cycle.

Furthermore, studies have indicated that melatonin levels, which are typically higher at night to promote sleep, may be lower in people with OCD. The reduced size of the pineal gland observed in this study could be related to these hormonal changes, but the exact nature of this relationship remains unclear.

“The pineal gland is important because it regulates sleep-wake cycles through the production of melatonin, a hormone that influences circadian rhythms,” Tabara explained. “This finding suggests that biological factors, particularly those related to the pineal gland and melatonin production, might play a role in OCD. While this study is small and more research is needed, the results hint at a potential link between disrupted sleep patterns, hormonal imbalances, and the development of OCD.”

While the study provides evidence of a structural difference in the brains of people with OCD, it has some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, with only 20 patients and 20 healthy controls. “Future studies with larger and more diverse groups are needed to confirm the results,” Tabara said.

Another limitation is that the researchers did not measure hormonal levels in the participants. “While the study found a smaller pineal gland volume in OCD patients, it did not assess the hormonal changes, such as melatonin or cortisol levels, which are important in understanding the gland’s function,” Tabara noted. “Without these measurements, it’s difficult to directly link the structural changes to the biological processes related to OCD.”

Exploring how pineal gland volume relates to sleep patterns, melatonin levels, and circadian disruptions in OCD patients could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the biological mechanisms behind the disorder. Ultimately, this line of research could lead to new therapeutic approaches that target the circadian system or melatonin regulation, offering potential new treatment options for people with OCD.

“The long-term goals for this line of research are to deepen the understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying OCD and to explore the role of the pineal gland and its associated hormones, particularly melatonin, in the disorder’s pathophysiology,” Tabara said. “By understanding the role of the pineal gland and circadian regulation in OCD, the research could contribute to the development of novel therapeutic strategies. This might include treatments that address melatonin imbalances or target the circadian system, potentially improving sleep and reducing OCD symptoms.”

“One additional point to emphasize is the novelty of this study. As the first investigation to examine the pineal gland volume in patients with OCD, it opens a new avenue for exploring the biological factors contributing to the disorder. Although the sample size is small and further studies are needed, this research adds an important piece to the puzzle of OCD’s complex pathophysiology.”

“Moreover, while the study focused on structural changes, future work should aim to integrate functional studies—like measuring melatonin levels, sleep patterns, and circadian rhythm disturbances—to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how pineal gland abnormalities might contribute to the behavioral and cognitive symptoms seen in OCD,” Tabara continued.

“Finally, we hope that this study encourages others to investigate underexplored neurobiological components of psychiatric disorders, which could potentially lead to better diagnostic markers and innovative treatments in the future.”

The study, “Reduced pineal gland volume in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder,” was authored by Murad Atmaca, Sevler Yildiz, Muhammed Fatih Tabara, Mehmet Gurkan Gurok, Mustafa Yildirim, and Hanefi Yildirim.