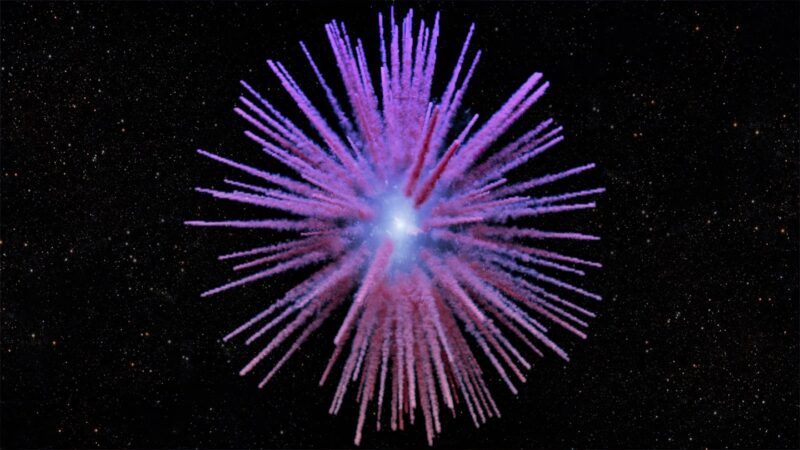

Some 6,500 light-years from Earth lurks a zombie star. It’s cloaked in long tendrils of hot sulfur. Skywatchers saw this star go supernova nearly 900 years ago. No one knows just how that explosion formed the tendrils now surrounding the dead star. But new observations capture the 3-D structure and motion of this debris.

“It’s a piece of the puzzle towards understanding this very bizarre [supernova] remnant,” says Tim Cunningham. An astronomer, he works at the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. That’s in Cambridge, Mass. He was part of a team that shared its new findings November 1 in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Astronomers in China and Japan first noted this supernova in 1181 as a “guest star” in the sky. But modern astronomers didn’t find the remains of that explosion, now called the Pa 30 nebula, until 2013.

Explainer: Stars and their families

When they did find the remnant, it looked weird. The supernova appeared to be a kind called type 1a. This type of stellar explosion involves a white dwarf star blowing up and destroying itself in the process. But in the case of Pa 30, part of the star survived.

Stranger still, the star was surrounded by spiky filaments. Those tendrils stretch about three light-years in all directions. “This is really unique,” Cunningham says. “There’s no other supernova nebula that shows filaments like this.”

He and his colleagues used a telescope at the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii to look at the nebula. They recorded how fast the filaments are moving relative to Earth. Then they built a 3-D model of those filaments and their motions through space.

The system is structured “kind of like a three-layered onion,” Cunningham says. The inner layer is the star. Then there’s a gap of one or two light-years, which ends in a spherical shell of dust. The final layer is the filaments, which emerge from the dust shell.

How the filaments formed remains a mystery. Also unclear is how those spikes have managed to stay in such straight lines for centuries.

Maybe a shock wave from the explosion ricocheted off the wispy material between this star and its neighbors. As the shock wave bounced back toward the white dwarf, it could have sculpted the material into the spikes astronomers see. But future studies will have to confirm or rule out that scenario.