A recent study by Stanford researchers has uncovered that people are more likely to believe and share news that aligns with their political views, regardless of whether it’s true. This “concordance-over-truth” bias was slightly stronger among supporters of Donald Trump and persisted across various education levels and reasoning abilities. Interestingly, resistance to true but politically opposing news proved stronger than susceptibility to fake but agreeable news, suggesting that political alignment often overshadows the truth in how people process information.

The findings have been published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

The researchers conducted this study to understand the extent to which political biases shape public beliefs and sharing behavior, especially during critical times like presidential elections. Recognizing that informed citizens are essential for a functioning democracy, they aimed to clarify whether people prioritize political alignment over truthfulness when processing news.

For their study, the researchers recruited 2,180 participants using the online platform Lucid from January 31 to February 17, 2020, aiming for a U.S. Census-matched sample based on gender, age, race, ethnicity, income, education, and region. After excluding 371 participants who failed attention checks or used mobile devices, a final sample of 1,808 participants remained.

The sample’s average age was 48.2, with 54.3% female and 45.7% male. Racial demographics included 72% White, 12.6% Black or African American, 7% Asian, and smaller percentages of other groups, with 12.8% identifying as Hispanic. Educationally, 70.4% had no bachelor’s degree, and politically, 37.6% supported Trump, 52.3% opposed him, and 10.1% were neutral.

The participants were shown 16 different news headlines: eight focused on Trump (half positive and half negative) and eight unrelated “filler” headlines to make the exercise appear more authentic. The Trump-related headlines varied in veracity, with half being real news stories and the other half being fake stories fabricated by the researchers. For example, fake headlines included outlandish claims such as Trump attending a controversial Halloween event dressed as the Pope, designed to be immediately recognizable as untrue, as well as more plausible but still fabricated news stories.

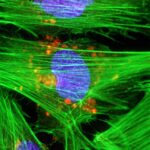

An example of the fake news stories used in the study. The researchers included both pro-Trump and anti-Trump news items.

Participants were asked to rate the truthfulness of each headline on a scale and to indicate how likely they were to share each one with others. After this, they completed a recall task where they tried to remember as many headlines as possible. Participants also answered questions regarding their political stance on Trump, media habits, and beliefs about their political side’s objectivity.

The findings of the study showed a strong “concordance-over-truth bias,” meaning that participants were more influenced by whether the headline aligned with their political views than whether it was factually accurate. Headlines that supported participants’ political positions were rated as more likely to be true, and participants expressed a stronger intention to share these headlines.

This bias appeared consistently across participants, regardless of their level of education or analytical ability, with a slightly more pronounced effect among Trump supporters. Additionally, the study revealed that resistance to true, politically discordant news was even stronger than susceptibility to sharing politically concordant fake news. This finding underscores that while people are indeed vulnerable to believing fake news that aligns with their views, they are even more likely to dismiss true news that challenges those views.

“To a surprising degree, politics can trump truth—in the present study, with regard to a presidential incumbent during a historic election,” the researchers wrote. “… By addressing methodological concerns in prior studies, our research found the impact of headline political concordance (i.e., partisan bias) to be 1.4–2.2 times greater than that of headline truth (i.e., accuracy) on ratings of headline veracity.”

The study further highlighted predictors of this bias, with some particularly notable results. Participants who held a strong “illusion of objectivity,” or the belief that their political side was more objective and unbiased than the other side, showed the highest levels of political bias. In other words, those who saw their own political group as less biased tended to display stronger partisan bias in their judgments of news veracity and sharing intentions.

One-sided media consumption also contributed to this bias, as participants who primarily consumed media sources aligned with their political views showed stronger tendencies toward the concordance-over-truth bias. Extreme views on Trump also heightened the likelihood of participants rating politically favorable news as true, irrespective of its factual basis.

“Understanding the problem of concordance-over-truth bias—its scope, severity, causes, and consequences—is essential for deciding on practical reforms and interventions,” the researchers concluded. “Our research suggests that the problem is significant. Confirmation bias and disconfirmation bias—in combination with one-sided news exposure and the prevalence of misinformation—seem to have given rise to a ‘post-truth’ world. A key step is to teach people to critically examine not only the news but also their own minds. Otherwise, we risk Carl Sagan’s feared vision of a future where people are ‘unable to distinguish between what feels good and what’s true.’”

The study, “When Politics Trumps Truth: Political Concordance Versus Veracity as a Determinant of Believing, Sharing, and Recalling the News,” was authored by Michael C. Schwalbe email the author, Katie Joseff, Samuel Woolley, and Geoffrey L. Cohen.